In the early 1970s, after ska and rocksteady, Jamaica found in reggae a style that was distinctive in both musical profile and content. It was a style that would go on to influence the identity of a generation and that was characterized by the social and political conditions of its time: the civil war-like process of independence, the harsh life in the ghetto, the fusion of slavery’s aftermath with Rastafarian culture. Supported by the technique of dub[1], roots reggae pushed for “righteousness”, which encompassed the elimination of social injustice and the critique of capitalism as well as cultural awakening and revolution.

In the early 1980s, that began to change. The failure of socialist experiments led by Jamaica’s Prime Minister Michael Manley caused the end of an exchange between producers, artists, and the social-political leadership. Violence and hardship in the ghettos increased. The ganja-based “ital culture” of the Rastafarians couldn’t fulfill its promise of salvation; cocaine and crack began to dictate the atmosphere at sound system parties. Following a phase of reggae’s global distribution, Bob Marley’s death in May 1981 left a vacuum in its wake. Marley’s success had been based on a stylistic variant that was in turn integrated into the aesthetics of mainstream rock by the pop industry—which meant that for most western, white audiences, reggae began and ended with him. After Marley’s death, reggae became virtually unmarketable and was dropped by many international labels. Producers gave up and started making dancehall, a style named after the venues where it had all started and where the now-disillusioned crowds wanted, simply, to have fun.

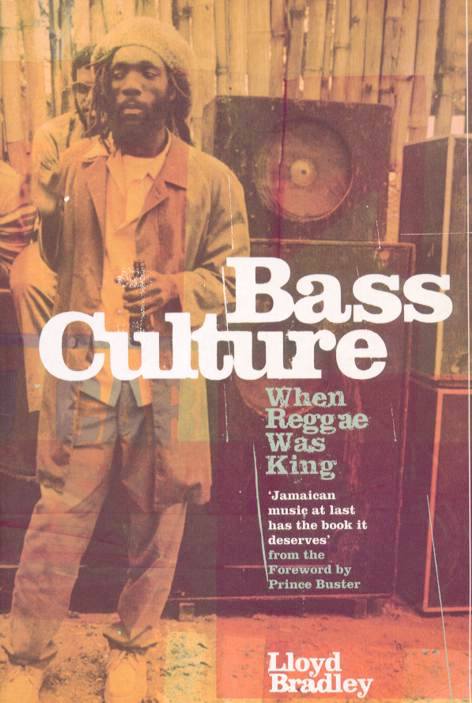

In Bradley’s view, that was the point at which reggae’s creative development deteriorated: roots came to a halt both musically and lyrically, was both stifled formally and squeezed economically. Finally, in 1985, the demand for both musicians and studios vanished almost overnight as people started composing backing rhythms using Casio drum machines. “Under Mi Sleng Teng”, a song produced by King Jammy and sung by Wayne Smith, was based on a rhythm without a bass line and as such changed the standards of the Jamaican music industry from the ground up. Now, people without any musical training could produce in their own homes—namely, they could remix already-made tracks ad libitum and sing over them. Bradley wasn’t the only one to show disapproval: Dennis Bovell complained that “reggae had slipped into its karaoke phase.”

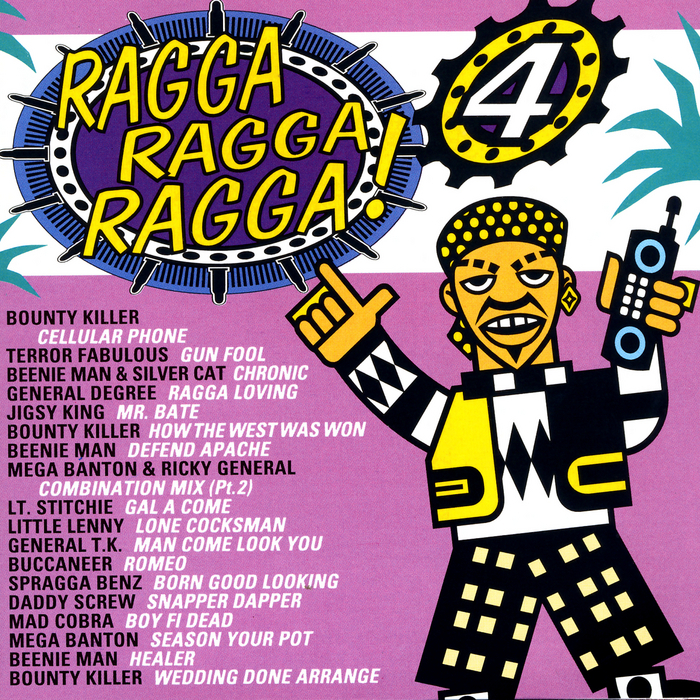

Digi-dub paved the way for 1990s dancehall—the tempos got faster, the “toasting” changed. The ubiquitous rhythmic chanting of rub-a-dub turned into ragga, a predecessor of rap and hip hop characterized by wordplay, humor, and frivolity. “Slackness” and “punaani” as well as “reality” and “rudebwoy style” crowded out “culture” and “consciousness”—the content and commercial draw of the music now revolved predominantly around sex(ism) and (the glorification of) violence. Buju Banton’s openly propagated homophobia in “Bye Bye Boom” (1993), for example, is one of the most regrettable manifestations of the often dreadful gender order in Jamaican society at the time. For Bradley, it was the loss of a relationship to history and the heedless attitude towards music-making that acted as evidence for the argument that reggae stopped developing in the mid-eighties altogether.

He may be partly right—the political and social messages of roots reggae became obsolete and irrelevant, and the style didn’t develop further. However, despite its artistically ruinous commercialization, dancehall was both a continuation and a fundamental turning point in a process of unravelling that engendered styles including jungle, drum’n’bass, dub techno, dubstep, 8-bit reggae, and bass music. Although some of these genres are unconcerned with the transmission of social or political messages, they have all absorbed important aspects of the reggae culture and continue to bring those aspects further—i.e., markedly outside of Jamaica[2]. They are the spawn of globalization and computer technology, both of which have given rise to a creative excess of repetitions, remixes, sampling, retro movements, reissues, and finally to the constant availability of everything.

When Bradley guessed at the turn of the millennium, then, that “in twenty years” no one would be excited to see a ragga reissue, he revealed little more than his own cultural pessimism and the limits of his own imagination. From today’s perspective, it seems clear that every decade since the foundation of reggae has gone on to produce ever more distinctive, relevant reggae. It is, though, important to choose selections carefully and to distinguish knowledgeably between roots, dancehall, and karaoke.

[1] see the Basslines column in zweikommasieben # 11

[2] see the Basslines column in zweikommasieben # 13

Lloyd Bradley (2000). Bass Culture: When Reggae was King. London: Penguin Books.

—

In this column, Marius “Comfortnoise” Neukom introduces book publications that relate in various ways to dub culture. He contextualizes each publication, describes its guiding principles, and expands on its author’s thoughts. An annotated version of this column with supplemental sound and text references can be found here.

More columns, other topics and also monthly charts can be found on Neukom’s blog Dubexmachina.