The passing of Genesis Breyer P. Orridge was a big moment for me. Immediately afterwards, I remember sharing stories with other fans and reading wonderful tributes from across the electronic music community. It is embarrassing to admit that I only recently read COUM & Throbbing Gristle co-founder Cosey Fanni Tutti’s autobiography Art Sex Music, published in 2017. I was shocked and disappointed to read of the complicated, traumatic, and at times abusive relationship she had shared with P. Orridge over their personal and working lives. P. Orridge’s own memoir Nonbinary is shortly due for release and we will see how this book will deal with this part of the artist’s life.[1] I have been spending the last few months going over old notes I had collected myself about P. Orridge and about her projects, like COUM, the highly influential industrial music group Throbbing Gristle, or the transmedia psychedelic project Psychic TV.

I had actually planned to interview P. Orridge back in 2010. Following a brief re-union, Throbbing Gristle were to play an All Tomorrow’s Parties event in England curated by Godspeed! You Black Emperor. I had flown in from Melbourne—but P. Orridge permanently quit the group shortly beforehand. The show was meant to go on, with remaining members Cosey, Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson, and Chris Carter performing as X-TG, but with the sudden death of Christopherson mere days before the gig, it never happened. In 2012, I got a second shot at an interview. P. Orridge was doing promo for an upcoming Psychic TV performance at Adelaide Festival. We ended up speaking on the phone for almost two hours in what turned out to be an intriguing, thought-provoking conversation, darting backwards and forwards in time, chronicling the many different eras of h/er career. Reading the words back now, it confusing to gush about work produced by someone who also caused a lot of pain. I wanted an opportunity, though, to use P. Orridge’s extracts from our conversation as a chance to praise and acknowledge not just P. Orridge, but everyone involved in those records, shows, and movements. In addition, revisiting the interview offered a possibility to reflect on the enduring fascination with the artists and h/er projects.

I was always drawn to the way P. Orridge was able to command attention. From dropping out of university, right up until h/er death, Genesis made it h/er mission to—for better or for worse—be front of mind, front page news, in the hearts or on the receiving end of the art world, fans, critics, and the unsuspecting public. And it all started with COUM back in 1969. Co-founded with Cosey Fanni Tutti, the performance art group COUM Transmissions was politically radical, designed to challenge and unsettle societal norms, and it caught the eyes of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin. What started as an “underground” rejection of the status quo ballooned into something bigger, even earning the praise of the British Arts Council.

Burroughs said to me in 70 or 71: “how do you short circuit control? That’s your task P. Orridge. To find out.” That was the beginning of the real evolution. COUM went from street theatre down to eventually just me, [soon to be Throbbing Gristle members] Cosey Fanni Tutti and Sleazy [Peter Christopherson]. We were starting to do roleplay switching… Cosey would start out as female and me as male, and then we’d switch. It got even more intimate with sexual taboos and transgression and who decides where and what is appropriate? Because it’s different in every country and culture. Therefore, it’s arbitrary. Therefore, it can be chosen. That was COUM.

We got more and more extreme and started to include bodily fluids and blood in our work as well as fake and real injuries… What is real? What is not? What is trickery? What is not? Where is the borderline between real and unreal? Awake and asleep? Alive and dead? Where are those lines and who decides? And are they even relevant? Suddenly, we found we were being accepted by the Arts Council and getting grants and performing at big arts events. We even represented Great Britain with Gilbert & George in Milan in 1976 [as part of the exhibition Arte Inglese Oggi].

When you are a kid you like a lot music that you later on put into question. Throbbing Gristle, however, is one band I can be proud to say I was truly into early in my life. I was a teenager completely hooked on the idea of them: a punk rock band without a drummer, music made almost entirely with machines, and live shows that messed with the audience in an almost brutal fashion. And the reason the band came into existence in 1976—forming as a reaction to the wider critical “acceptance” that COUM was receiving—is, gorgeously, fundamentally punk.

As soon as all of that [wider attention] started to happen, we just thought: “this isn’t what we want. We don’t want to become another member of the establishment; we have to change direction. What else can we not do? Ahh, none of us can play instruments! Let’s be a rock band! Let’s reconstruct rock music!

The first thing we all agreed on was no drummer. Drummers inevitably set up certain patterns that are so traditional that the responses of the other musicians are sort of drawn to expected techniques and sounds. We wanted to get away from that and mirror the world we lived in, which was post-war Britain. We grew up playing in the bomb craters in Manchester. We’d seen the results of war. We wanted our work to be a reflection of the Western European experience after a huge war. What was relevant to us? The decay and the industrial landscape. The steam engines we’d go past on the way to school were being cut apart and turned into scrap metal. The mills that used to make cotton and natural fabrics were closed because of new nylon and manmade fabrics. We saw this contradiction. This fake modernity of [former British Prime Minister] Harold Macmillan’s slogan “never had it so good…”.

There was nothing relevant to the youth of the time at all. We experimented with cut-ups to completely make it impossible for our conscious, habituated memory of music to control what we play. If we do cut-ups using tape recorders and so on, then we’ll create music that’s new. Music that is irrational and illogical to the average ear. To reflect what we saw as the decay of British power, and capitalism, and fake freedoms.

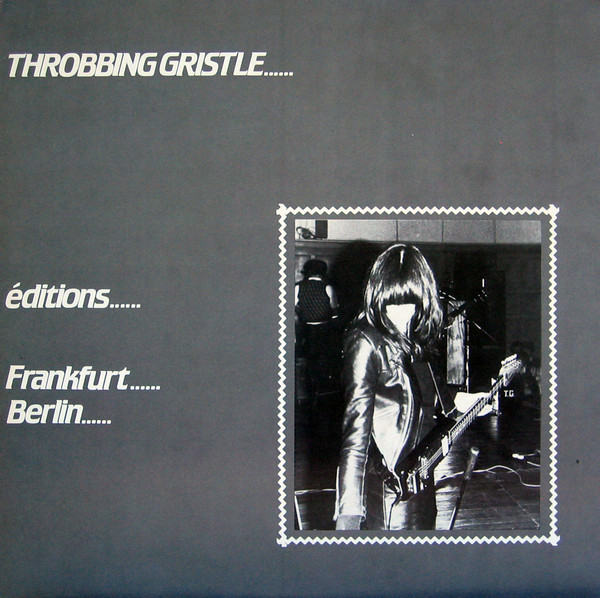

Throbbing Gristle could shred like no other band making electronic music back then. The first record of theirs I heard was Éditions Frankfurt-Berlin, a live bootleg released in 1983. I was in a record store in Tokyo and picked up the album because I thought the photo of Cosy on the cover—dark hair, leather jacket, face blanked out in light—looked the most rock and roll it is possible to look. She was holding what appears to be a Steinberger guitar (though it is more likely something they made in the shed). The first track on the record—a ten minute live rendition of “Discipline”—opens with Chris Carter’s pounding drum machine, Cosy generating some unrecognisable guitar sounds and P. Orridge demanding “We need some discipline in here!” To me, this was not only completely new music with self-build machines, but it was total chaos, total carnage.

In those days there were no samplers, no synthesizers. Chris Carter, who is an electronic genius, built his own synthesizer. Sleazy built the equivalent of a sampler by using eight Walkmans running through a keyboard that could create rhythms allowing him to jam with his fingers. The tapes could be anything. He did lots of field recordings; he bugged the offices of a mercenary group and recorded them. He recorded illicit gay sex in public toilets and added all those things in subliminally—all of that was directly influenced by Burroughs and Gysin. We also built all the speakers ourselves, and they were loud. For my bass guitar we had bass bins taller than me that we could climb into. And four 4×12 guitar amps as my monitors! A 200-watt bass amp just to monitor my bass so when we hit it, it made your clothes move.

Throbbing Gristle gigs were wild, from their early shows in the late 1970s right up until their reunion performances in the in the early 2000s. The creativity in conceptualising what their live “show” actually was, combined with the intensity and sheer volume of their playing, makes Throbbing Gristle the greatest live band in the history of electronic music. A friend of mine—Richard Fearless—has spoken about Throbbing Gristle being the first electronic band to have a punk energy. He told me the first time he ever saw them in London, the show started with the band coming on stage and slamming the house lights on. It was blindingly bright, deafeningly loud, and, in his account, incredible. In the interview, P. Orridge reflected the following way on Throbbing Gristle’s shows:

We used to find unusual places to play. We played in a closed down school run by Spanish anarchists. It was semi-derelict, and they’d created a rough stage out of scrap wood and burned bonfires inside the building to keep it warm. We’d use halogen lamps pointed at the audience as one of our ways of rejecting the idea of “audience looks at band/band looks at audience.” Instead, it was people almost blinded by lights so they had to address the music and the sound.

We once played inside a square cube of scaffolding covered in tarpaulins. We had cameras on us so the audience could see us playing on some monitors inside a building. So if you wanted to see us play, you had to be inside watching televisions, where there was no sound. If you wanted to hear us play, you had to go on the roof of the building and look down five floors [unable to see the band].

Once for a gig at Butler’s Wharf [in London], we had two PAs. One at the front was ours, and a normal one at the back which had a feed of our mix… For the audience, if they tried to back away from the extreme volume, it actually got louder! We did all kinds of things to mess with the idea of the band being the focus and the music being the really important effect. We thought of it as functional, metabolic industrial music.

P. Orridge has described Throbbing Gristle as a project built on anguish. Psychic TV, the experimental, psychedelic group s/he led from the early 1980’s through until h/er death, had a very different vibe. Together with its community-led Temple ov Psychick Youth fellowship, the group set out to create art that was joyful, friendlier, happier. Psychic TV featured a revolving door of members and collaborators, it seems, were brought in to work on music at just the right time. Records released between 1988 and 1990, like Jack the Tab—Acid Tablets Volume One, Tekno Acid Beat, Towards Thee Infinite Beat and its remix album Beyond Thee Infinite Beat have been widely credited precursors and influences on the acid house movement.[2] To P. Orridge, the music of Psychic TV was a complimentary piece of something much bigger. The community-minded work that the collective was undertaking throughout the UK and beyond, seemingly, was just as important as any musical output.

In Throbbing Gristle, all the lyrics and melodies were dark… If you can call [the musical sequences in] “Maggot Death”, “Blood Bait,” or “We Hate You (Little Girls)” melodies! In those days, between ‘75 and ‘81, we were really angered and disgusted, just as much as all the people who formed punk bands. Disgusted at the hypocrisy, and the bigotry, and the attempt to continue this fake concept of the perfect England. The sense of helplessness and the inability to truly change things leads you to look for experimental alternatives of your own and to analyse what it is you would like life to be; to think about what it is you would like to see the human species do to evolve; to take away it’s primitive, disgusting love of violence, depression, power, control, and riches for its own sake—the things we believed was destroying the world. [Psychic TV] was our attempt to look for ways to set up communities and alternative networks where those who have enough in common could recognise each other.

Another theme in extreme contrast to the undeniably abrasive artistic output that began all those decades ago with COUM and Throbbing Gristle is the love story of P. Orridge and Jacqueline Breyer aka Lady Jaye. Their relationship was beautifully captured in the 2011 documentary film The Ballad of P. Orridge and Lady Jaye. And the “Pandrogyne Project,” P. Orridge and Breyer’s lifelong pursuit toward fusing and becoming one single being, represented commitment in its purest form.

It started out as instinctive. But it’s Lady Jaye who deserves the notoriety. The first day we met was in a dungeon where she worked as a dominatrix. We’d been up for three days on ecstasy and finally crashed on the floor amongst all the torture instruments. She was being told things like, “Don’t go in there… The guy in there is a weird English artist and you don’t want to go near him.” So of course she’s thinking: “I must meet this person!” When we woke up, we heard voices and we saw this woman walking back and forth in the other room. She started to undress, smoking her cigarette very glamorously, as she changed into a fetish outfit. She dressed me in her clothes the very first day I met her. We found ourselves saying “If we can be with this woman for the rest of our lives, that’s all we want”. We fell in love at first sight.

It was so all-consuming that we wanted to become each other, to never be separated. So to represent that obsessive desire, we began to dress alike and do our hair alike. Then we thought about it more theoretically, and thought about what Burroughs had said… “Where is control?” We thought control is DNA. DNA is the ultimate recording device. It’s the biological tape and in order to cut it up, you have to deny its power. How do you do that? By changing yourself in a way that DNA wouldn’t make you. By rejecting the body that DNA would give you. It wasn’t that we wanted to look identical, so much as, we didn’t want to grow to be the body that DNA wished us to be.

We started to do little things at the beginning. We got tattoos of her beauty marks on my face. We got our lips made the same size. She got her eyes surgically made more like mine. Then her nose and her chin. Then we got our cheeks done to match. Then on Valentine’s Day in 2003, we went for it with matching breast implants. We woke up holding hands, looked down and thought: “these are our angelic bodies.” At that point it became a much more serious problem. We were out of the binary system of male/female, which is what we wished to do. We wanted to reject inherited systems of thought, inherited values, archetypes and stereotypes, genders—to truly build ourselves as two halves of one. That’s what we called it the pandrogyne: the positive androgyne, the powerful androgyne, the political androgyne.

Our conversation ended when I asked Genesis about being referred to as a “cultural engineer,” and the response that followed was my favourite. Casually delivered almost as if reading a shopping list, Genesis reeled off trends and movements—now enormous in their global adoption—that s/he feels proud to have been an early part of. As a young fan, I think this is what I really loved about Genesis. It is the way s/he would speak to being first to uncover these different parts of culture, presenting them in new, challenging, ear-bleedingly loud ways. And to do so with unwavering confidence, swagger, and drive. S/he lived a seemingly open, public life, and for decades nothing was off limits… Though as Fanni Tutti’s recent revelations have proven, perhaps there is still so much we have yet to learn.

On September 3rd, 1975 in London Fields Park we said to (industrial music pioneer) Monte Cazazza “this music that we’re making needs a name”. He said, “you keep saying industrial”. It was Monty who pointed out to me that I’d named this genre of music. The Modern Primitives book about piercing and tattooing was researched by me. We arranged for most of the interviews and most of the content. In those days there were only about three people in the world doing that kind of tattooing. That book changed the world. Piercing, tattooing, and liberation of the body and the skin became a way of expressing one’s self. The innate power of it remains. And now every town and village in the world has a piercing and tattooing expert. We were very involved in the early days of rave. We predicted in the Industrial Culture Handbook that occult magic would become trendy again, and be reassessed, which it did.

That’s being a “cultural engineer.” Literal manipulation of the culture almost subliminally, hiding behind the camouflage of being a silly eccentric rock star. Lady Jaye used to call it “dazzle camouflage.” You do it so obviously in front of people, they don’t see what you’re doing.

Special thanks to Alex Solman for allowing us to use his illustration for the article.

[1] Any retrospective should call the abusive behaviour, and none does a better job than Luke Turner’s exceptional piece for The Quietus.

[2] A personal career highlight of mine happened in 2017 when Jack the Tab producer Richard Norris remixed one of my band Black Cab’s songs, “Empire States”.